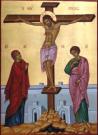

The Cross-Shattered Christ: Chapter Three

It's been a good, but not overly easy, reading of Hauerwas’s “The Third Word,” in his Cross-Shattered Christ. What follows is a summary.

It's been a good, but not overly easy, reading of Hauerwas’s “The Third Word,” in his Cross-Shattered Christ. What follows is a summary.The “word from the cross” for reflection in the third chapter comes from the Gospel of John: "When Jesus saw his mother there, and the disciple whom he loved standing nearby, he said to his mother, "Dear woman, here is your son," and to the disciple, "Here is your mother." From that time on, this disciple took her into his home" (19.26-28).

Hauerwas first emphasizes that these words—and nearly every concern Jesus had for his family, and his mother included—are not examples of Jesus as an romanticized dying son . We note, for example, that Jesus “addresses his mother as ‘Woman,’ the same address he uses to respond to the woman of Samaria who had five husbands (John 4) and the woman caught in adultery (John 8). Naming his mother as “Woman,” as he did at the wedding of Cana, is “not a sentimental appeal to his “mom” (50) In fact, Hauerwas notes, “it must be admitted that none of the Gospels portray Jesus as family-friendly” (50). Jesus insists that “whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother” (Mark 3). Remember it is Jesus who says, “Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, even life itself, cannot be my disciples” (Luke 14). Jesus is thus not a so-called “normal” family man; he never married nor had children.

However, not wishing to call attention to Jesus’s “anti-family remarks to denigrate his address to Mary from the cross,” Hauerwas spends the rest of the chapter stressing that Mary is not simply another mother; rather—and this is important—“Mary is the firstborn of the new creation” (51). Hauerwas says it bluntly and clearly, if Mary had not said Yes to Gabriel, we would not be saved. Raniero Cantalamessa, Hauerwas is convinced, has rightly given her the biblical honor she deserves when he titled his recent book, Mary: Mirror of the Church. Cantalamessa has made the fascinating observation that where as Jesus is often recommended to us as the New Adam, New Moses, and New David, nowhere is Jesus the New Abraham. The reason, Cantalamessa suggests, is that Mary is our new Abraham: Just as Abraham did not resist God’s call to leave his father’s country to go to a new land, so Mary did not resist God’s declaration that she would bear a child through the power of Holy Spirit. And just as Abraham came to understand that his son Isaac was to be sacrificed, so Mary at the cross, like Abraham, experiences the sacrifice of her son. With this great difference: Mary’s Yes could not save her son from being the one born to die on a cross. Mary is thus “the true daughter of Israel,” the daughter/mother “tested as no one in Israel had ever been tested.” Mary witnesses the immolation of the Son; it is she who enters “the darkness that is the cross” (52).

Now it is this Woman whom Jesus charges to accept and regard John, “the disciple whom he loved,” as her very own son. Mary is to adopt John, love him, and take care of him as her own child. And John, in turn, is to take Mary as his mother and take care of her. Mary, Hauerwas suggests, is thus “the first great representative” what we are and do as the Church, the loving-each-other community of Christ. What we see in this exchange is nothing less than the beginnings of the Church, the community of those who, in Christ, take care of one another.

For this reason, Hauerwas asks us not to “repress the role of Mary in our salvation” (53). Because Mary is a part of the Church, a holy and excellent member, above all others but, nevertheless, a member of the whole body, we ought not “compromise Mary’s home,” her place in our community of faith. We will want to remember her and her Song of triumph, the so-called Magnificat. Mary-like we “must live by hope—a hope that patiently waits with Mary at the foot of her son’s cross” (55). In Christ God “re-members” with Mary; that is, God joins with her in God’s re-membering; together in Christ we are members one of another, and that, as the Protestant theologian Hauerwas says, is why we pray “Hail Mary, full of grace, pray for us.”

Most Protestant Christians have not taken the time or made the effort to think about the role of Mary in the Church's theology and prayer life. If you're interested in beginning such an exploration, you may want to visit Holy Mary, Theotokos or comment on your own understanding of Mary's place in salvation history. If you wish to do some prayerful pondering about the Blessed Virgin Mary, visit What about the Virgin Mary? As a Christian informed by the Lutheran tradition (and worshipping among Methodists, Baptists, and Episcopalians, and Roman Catholics) I'd be glad to offer more reflections on the Blessed Virgin Mary.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home