Responding to Mason's Post on Wesley's Conviction that "a concept of sin was central to Wesley's message, and one of the keys to his success."

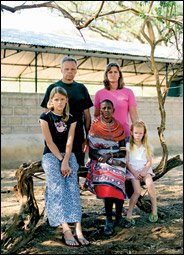

I'm not sure my response is apropos to your posting, Mason, but your comments on reading about Wesley's theology reminded me of an article I read on the plane while coming back from Hawaii. In the magazine section of yesterday's New York Times, Danial Berger writes an essay, "The Call," in which he describes in detail how an evangelical missionary family is trying to share the Gospel with the Samburu, seminomadic herders of cattle and camels and goats. Culturally, the African Samburu have little or no sense of sin; as a consequence, missionary Rick says that the first lesson he has to impart, the first truth he has to instill in the people, is 'a sense of sin and separation from God'- a separation that could be reconciled only through Jesus. " That sounds like something Wesley would wish to say. But imparting a sense of sin to the Samburu is exceptionally difficult. Berger, speaking for missionary Rick, explains why:

I'm not sure my response is apropos to your posting, Mason, but your comments on reading about Wesley's theology reminded me of an article I read on the plane while coming back from Hawaii. In the magazine section of yesterday's New York Times, Danial Berger writes an essay, "The Call," in which he describes in detail how an evangelical missionary family is trying to share the Gospel with the Samburu, seminomadic herders of cattle and camels and goats. Culturally, the African Samburu have little or no sense of sin; as a consequence, missionary Rick says that the first lesson he has to impart, the first truth he has to instill in the people, is 'a sense of sin and separation from God'- a separation that could be reconciled only through Jesus. " That sounds like something Wesley would wish to say. But imparting a sense of sin to the Samburu is exceptionally difficult. Berger, speaking for missionary Rick, explains why:But few around Kurungu seemed much interested in [the missionaries'] religion. The Samburu faith is monotheistic. It holds its own sacred history in which, I was told, humankind had once been linked to Ngai by a ladder made of leather. Ages ago, a Samburu man, enraged by the death of his herd, cut the ladder, and ever since the people have been disconnected from their deity. Yet when the Samburu spoke to me about Ngai, they evoked not a divinity that is abstract and removed but one that is, though invisible, close at hand, especially on the steep mountains that bound the valley, and most especially on a particular set of ridges and rocky peaks known collectively as Mount Nyiru. This, the tribe's most hallowed mountain, about 9,000 feet high, rises immediately to the west of Kurungu. It looms over the family's backyard. Ngai is up there, taking care of his people. He had granted the Samburu the knowledge of how to survive on cow's blood, Andrea and his crew said. And he was forgiving when the people did wrong. He had placed a spring at the spot where the leather ladder had been cut. The Samburu told me that their religion makes no prediction of a messiah. They didn't seem to feel the need for one.

One might wish to ask: can the Gospel of Jesus be relevant to a people who do not, for cultural and historical reasons, find it nearly impossible to sense separation from God because of sin? Must we somehow first make them "western" or "Judaic" before they can appreciate the Gospel? Or can the Gospel somehow also speak to people who have little or no sense of sin? Might it be possible to talk about separation from God apart from an understanding of sin? For example, could one make the Gospel relevant to someone or some people who feel the sadness of separation (say perhaps that of a young child from its parents, that of husband from his wife and children, that of a immigrant from his homeland) without feeling or experiencing a sense of sin? In other words, must alienation from God--and wonderful union with God--always be require a notion of sin and subsequent forgiveness as Wesley requires?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home